Vol 2 | Issue 1 | Jan – June 2017 | Page 14-26 | G S Kulkarni, Vidisha Kulkarni, Ruta Kulkarni, Sunil Kulkarni, Milind Kulkarni

Authors: G S Kulkarni [1], Vidisha Kulkarni [1], Ruta Kulkarni [1], Sunil Kulkarni [1], Milind Kulkarni [1].

[1] Swasthiyog Prathisthan, Miraj, Maharashtra India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. G S Kulkarni

Swasthiyog Prathisthan, Miraj, Maharashtra, India.

Email: gskorth@gmail.com

Abstract

Terrible triad (TT) is traditionally an injury that is been well know but poorly understood. Most of the poor results are due to lack of understanding of the pathoanatomy and formulate a plan for individual cases. Bony articulations as well as the ligamento-tendious structures are injured along with added complexity of the elbow joint, the terrible triad is not a simple injury to comprehend. The current review focusses on the basics of pathoanatomy and relevant decision making protocols along with details of various treatment modalities. we also share our personal experience of 20 cases of terrible triad and also our preferred method of treatment

Keywords: terrible triad, radial head, medial collateral ligament, external fixator, functional outcomes.

Background

Terrible triad (TT), a complex elbow dislocation, is a combination of a radial head fracture, dislocation and a coronoid process fracture. Historically, TT has had consistently poor results; for this reason, it is called the terrible triad injury. The eponym is coined by Hotchkiss[1]. The rate of subluxation or dislocation after operative treatment of these injuries has ranged from 8% to 45%[2].

In a simple fracture without dislocation elbow, medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), capsule, muscular elements are torn and there is dislocation of ulno-humeral and radio-carpal joint. When both joints are reduced closely, all ligaments and capsule heal well; but not so with TT which needs surgical repair of all torn tissues. TT injuries are seen more commonly in adults and are rare in children’s.

During the last 2 decades better understanding of relevant anatomy and biomechanics of stability, restoration of injured primary and secondary stabilizers of elbow, improved surgical technique have given excellent results; and operative treatment of this injury has evolved to include restoration of radiocapitellar contact (via fixation or replacement of the radial head), reattachment of the origin of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) to the lateral epicondyle, with fixation of the coronoid fracture, and medial collateral ligament (MCL) repair when indicated[2].

These techniques have decreased the occurrence of subluxation or dislocation after operative treatment of a terrible triad injury[3-5].

TT is now no more terrible; however, despite best attempts of reconstruction by even experienced specialists final outcome may not be so satisfactory. Tanna[6] has published a series of 9 cases. He presented cases in which the radial head could not be repaired due to comminution, head was resected and elbow was immobilized for 6 weeks with satisfactory results. We also did resection of radial head in 7 cases with repair of LCL, coronoid, MCL and of both flexor and extensor muscles, with repair of all other primary and secondary stabilizers(except radial head) and elbow was stabilized by orthofix hinged external fixator for 6 weeks, with comparable results. Perhaps head resection is indicated in developing countries, where head could not be repaired or replaced due to various specific conditions in developing countries, described below. Planned post-operative care is needed to reduce complications. The goal of treatment for terrible triad injuries is restoring the bony anatomy and reconstructing the ligamentous restraints of the elbow to provide enough stability for early elbow range of motion and prevent elbow stiffness. Early management has a favorable prognostic factor for outcome. Delayed presentation> 2 weeks has poor outcomes. Understanding the patho-mechanics of this complex elbow dislocation may improve diagnosis and treatment of these injuries.

The purpose of this paper is to review current management of TT, especially, our experience and the results of resection of radial head in TT

Relevant Anatomy

An understanding of the anatomy of the structures of elbow is paramount to the successful treatment of TT. The coronoid process provides an important anterior and varus buttress to the elbow joint. Ulno-humeral joint is the key element of elbow stability. The coronoid is thought to be the most significant determinant of stability of the elbow joint[7].

Although the coronoid fracture was once described as an avulsion fracture, it is now considered most often to be the result of shear forces caused by posterior translation against the humeral trochlea. Tip of coronoid does not have any muscular attachment.

The anterior bundle of MCL, a primary stabilizer of elbow stability originates from the antero-inferior aspect of the medial epicondyle, and is inserted in to the sublime tubercle at the base of the coronoid process [8]. Lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL) is inserted in the supinator crest, distal to sigmoid notch and it originated at lateral epicondyle, which is the isometric point[9]. The radial head is a slightly elliptical structure. With the forearm in neutral rotation, the lateral portion of the articular margin of the radial head is devoid of hyaline cartilage. This is the safe zone for plating from radial head to shaft, when the forearm is in mid pronation position.

The flexor and extensor muscle and the joint capsules are secondary stabilizers of the elbow. The muscular system provides dynamic stability against valgus and varus forces.

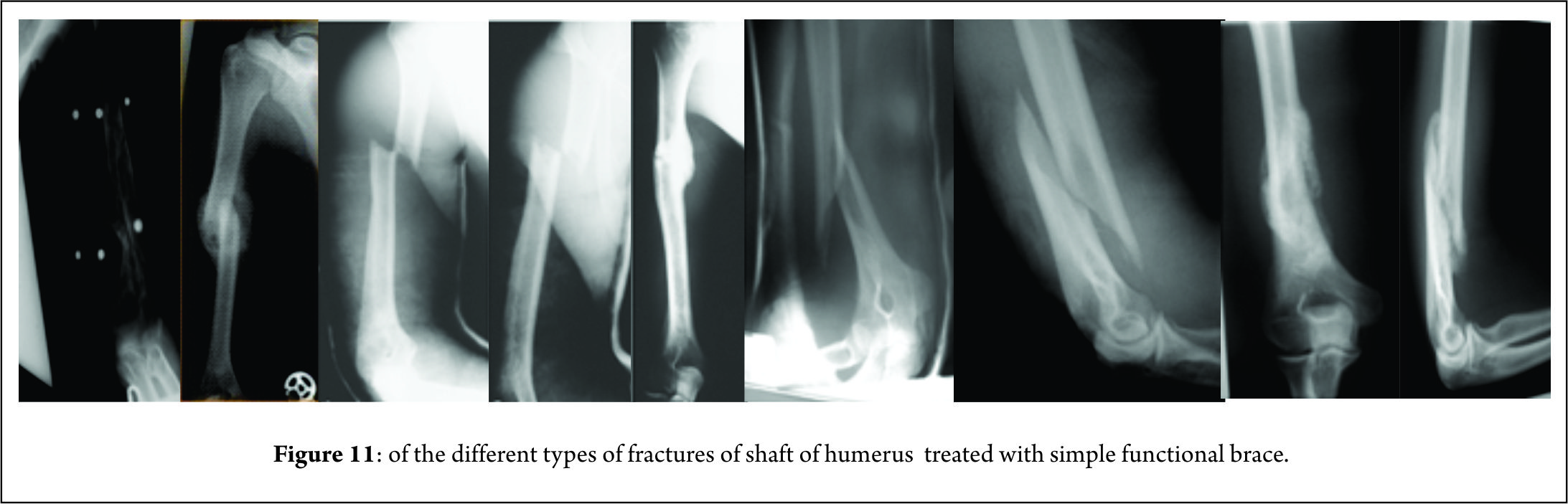

Fracture classification

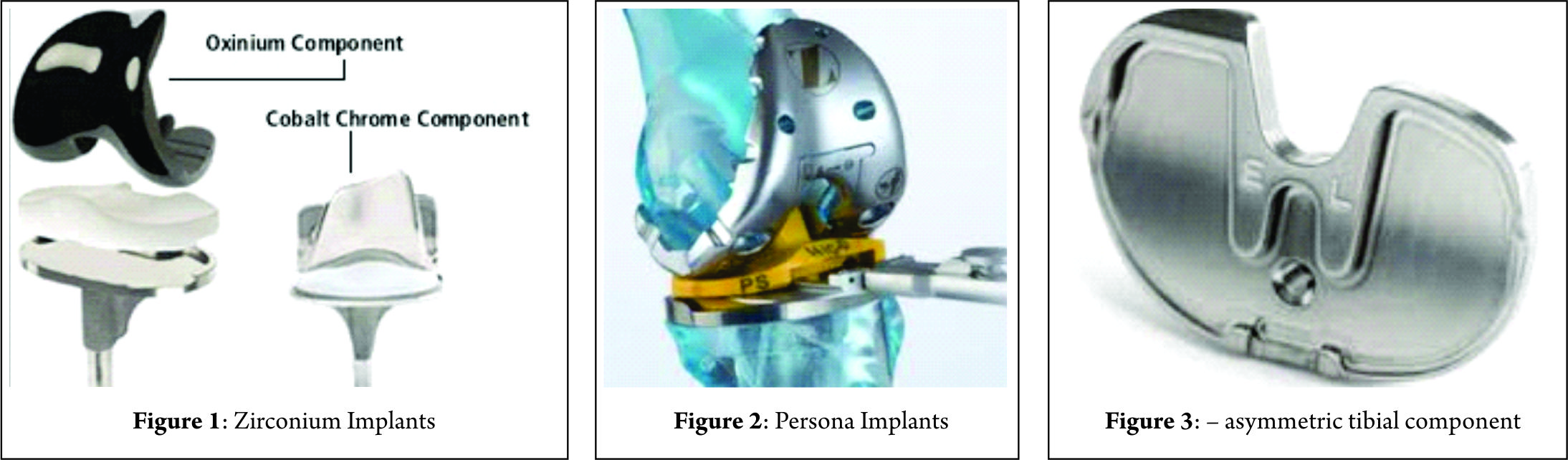

Fracture classification is important from management of TT point of view. Mason[10] classified radial head fractures into three categories: type I, non-displaced fracture; type II, displaced partial articular fracture with or without comminution; and type III, comminuted radial head fracture involving the whole head.

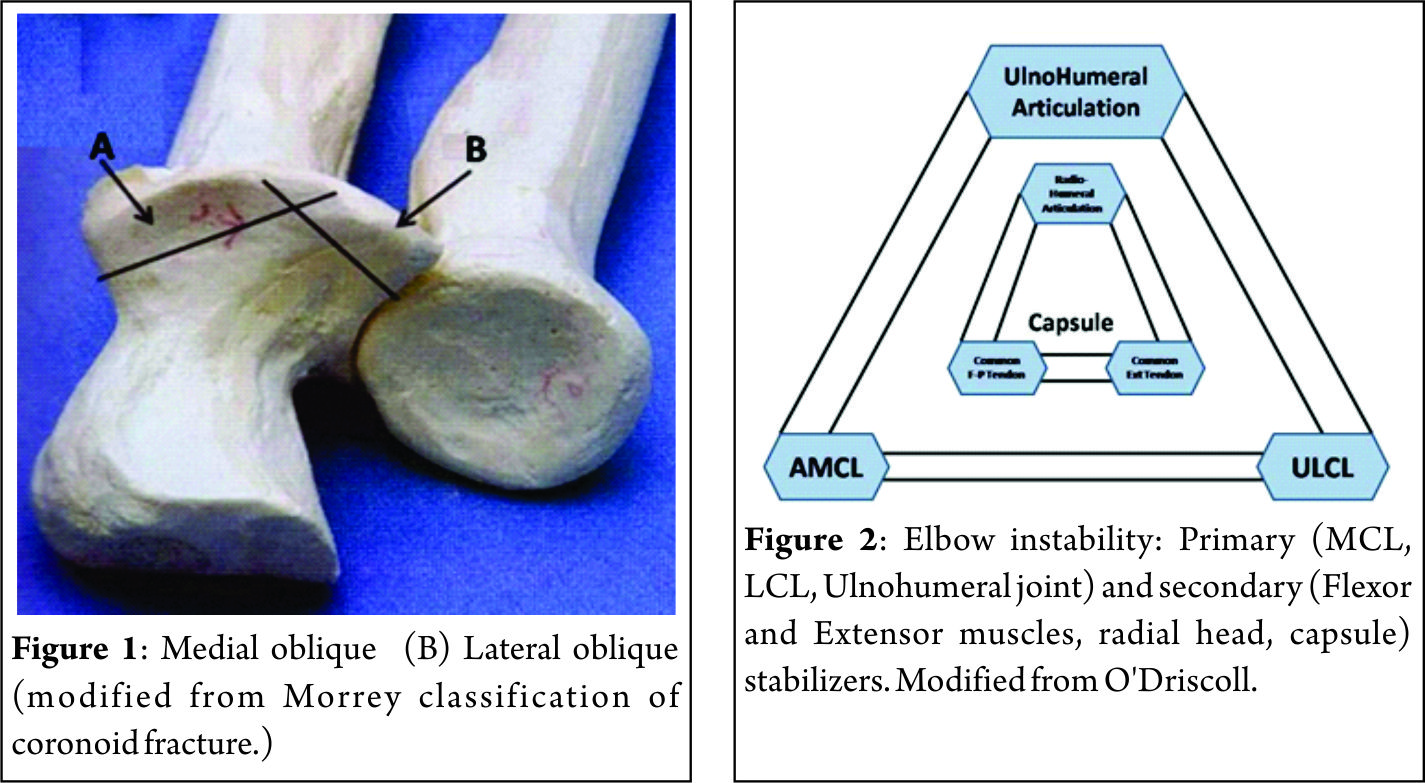

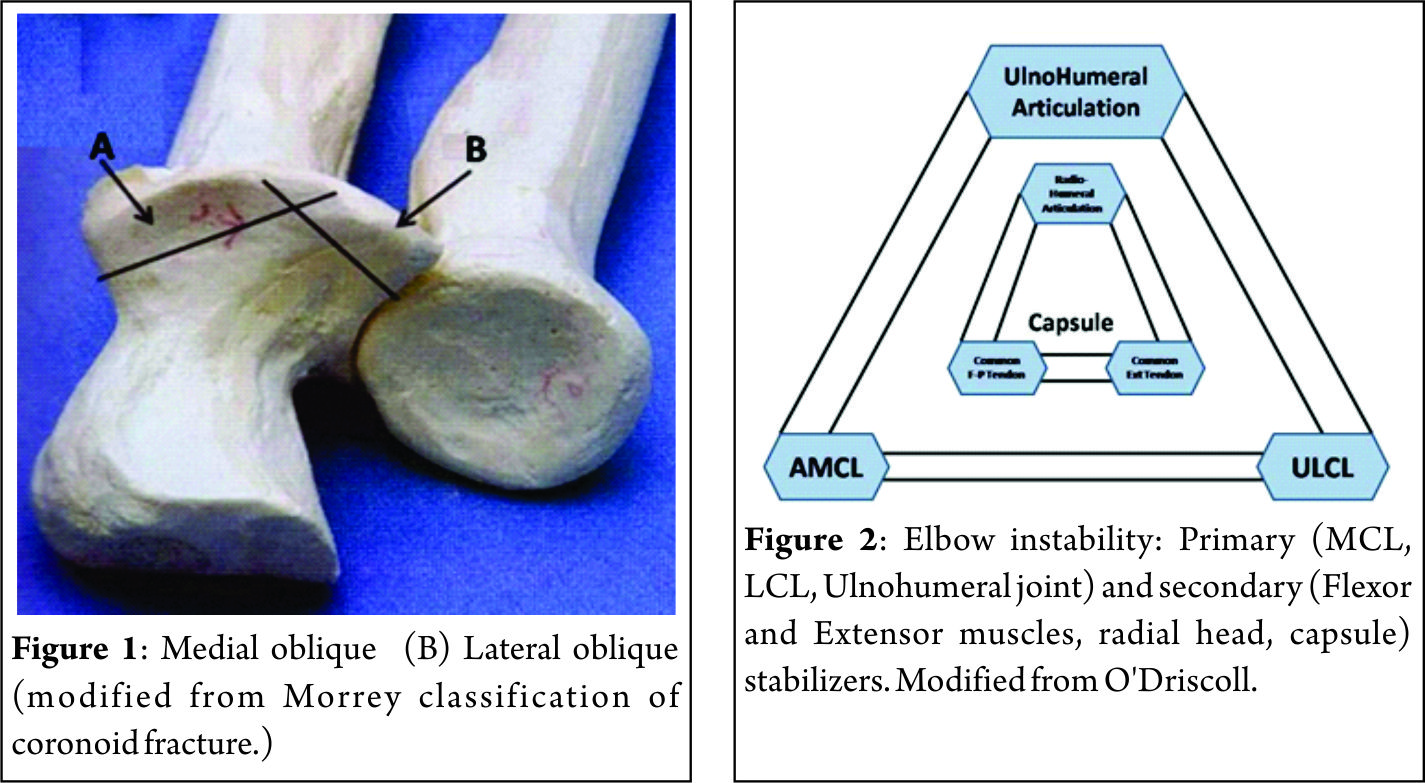

Regan and Morrey[11] classified coronoid fracture (Fig.1) into following 3 types –

Type I – Fracture involved an ‘Avulsion’ of the tip of the coronoid process.

Type II – Fracture involved a single or comminuted fracture representing <50% of the coronoid process.

Type III – Fracture involved a single or comminuted fracture of >50% of the coronoid process. Currently, the simple modification of the original classification includes medial and lateral oblique fractures. However, it has been recently shown that for practical matters, the original classification system is probably adequate as a basis of our clinical decisions[12].

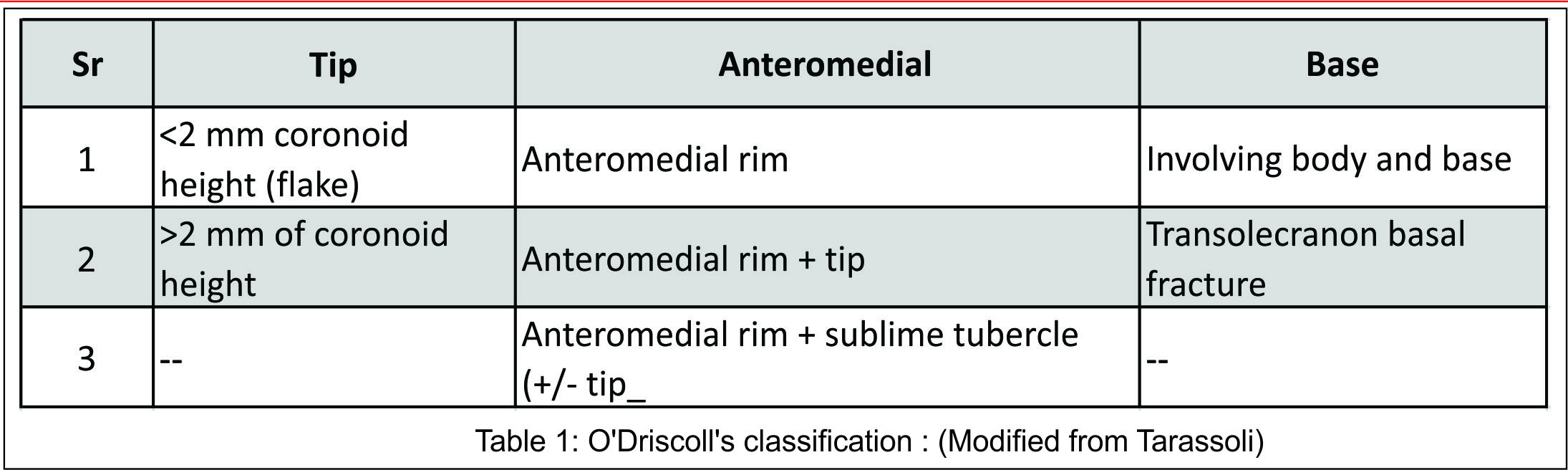

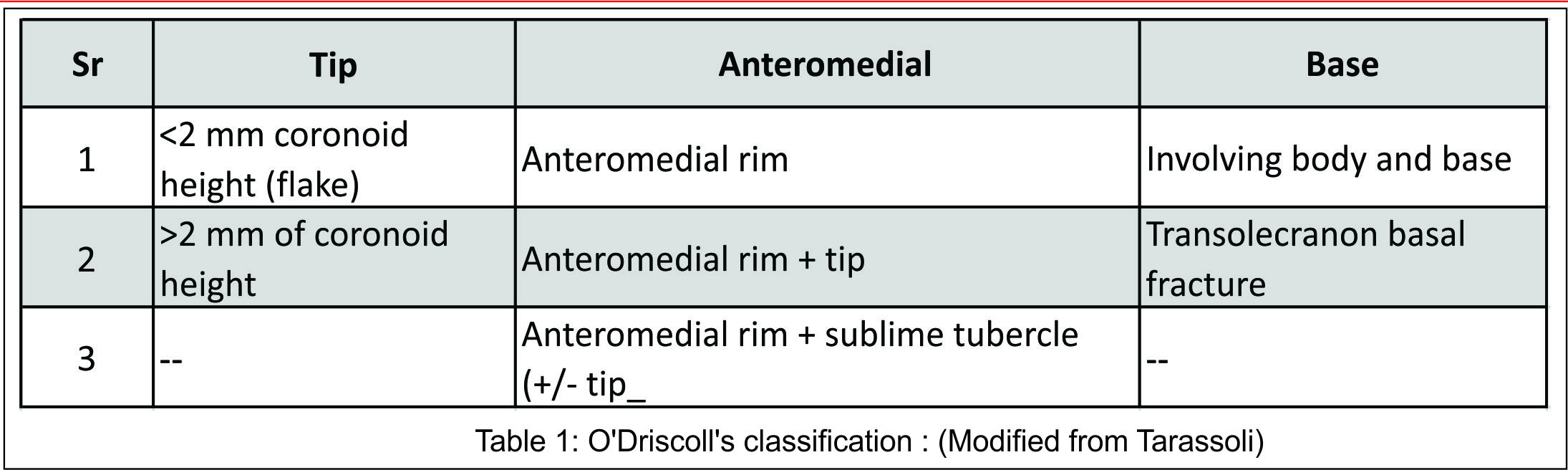

O’Driscoll’s classification is more applicable to management as it emphasizes the importance of the anteromedial facet injury, which causes instability.

His classification is as shown in table 1: (Modified from Tarassoli) [13]

Fractures of the anteromedial facet are divided into three subtypes. Anteromedial subtype 1 fractures do not involve the coronoid tip and extend from just medial to the tip to just anterior to the sublime tubercle. Subtype 2 fractures are subtype 1 with involvement of the coronoid tip. Subtype 3 fractures involve the anteromedial rim of the coronoid and the sublime tubercle.

Doornberg and Ring Demon[14]- stated that fractures of the antero-medial facet of the coronoid could result in increased instability, even without a significant overall loss of height. They recommend fixation of these fractures through an alternative medial approach, even when the fracture is very small[14].

Biomechanics

Understanding of biomechanics of elbow instability is of paramount importance to treat TT. The elbow’s stability depends on static and dynamic stabilizers. Static stability is maintained by osseous and capsule -ligamentous restraints, whereas muscles crossing the elbow provide dynamic stability.

Beyond 30° of flexion, the coronoid process provides substantial resistance to posterior subluxation or dislocation[15].

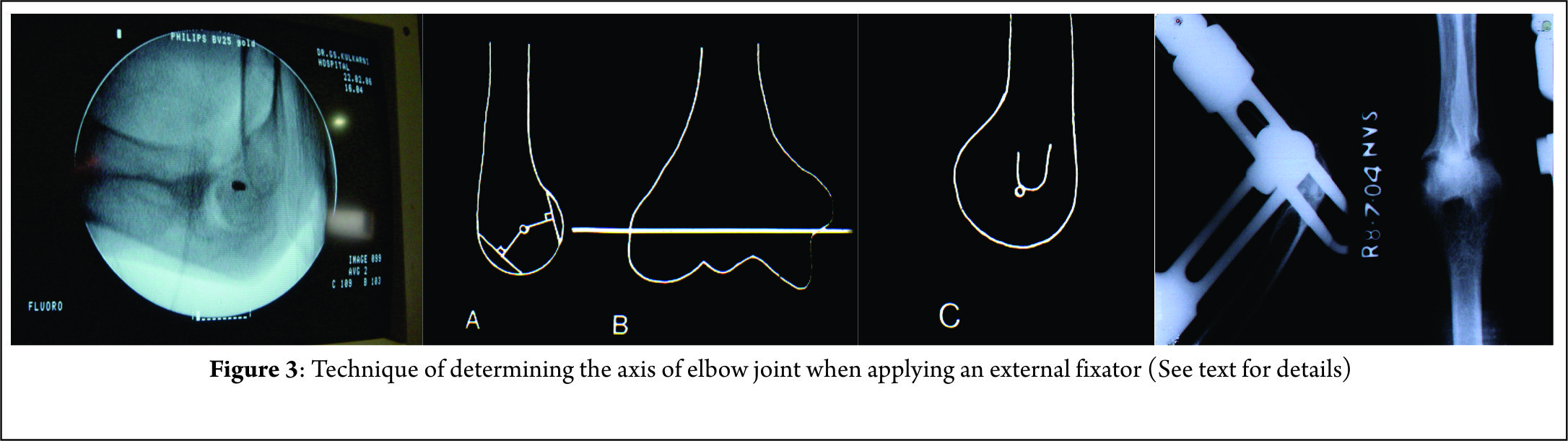

Elbow stability is due to primary and secondary stabilizers due to symbiosis of bony and ligamentous anatomy. (See Fig.2.)

Primary stabilizers are

(1) The ulno-humeral articulation

(2) MCL (the anterior bundle),

(3) LCL complex (the ulnar lateral collateral ligament).

The secondary stabilizers are

(1) The radio-humeral articulations,

(2) Common flexor tendons, Common extensor tendons,

(3) The capsule.

Small fractures of the tip involving 10% of the coronoid process have been shown to have little effect on elbow stability in cadaveric biomechanical studies and may be neglected.

When residual instability was present after LCL repair and radial head repair or replacement, repair of the MCL was more effective than fixation of small coronoid fractures in restoring elbow stability[16]. Posterior displacement of the ulno-humeral joint is not affected until 50% of the total coronoid height is removed when the ligaments are intact[17], but smaller fractures can result in instability if there is a deficiency of the MCL[18]. Coronoid fragments more than 10% of coronoid process require surgical fixation.

Functions of radial head are – (1) Radial head is an important, anterior and valgus to buttress, (2) It also tightens the lateral, collateral ligament and provides varus stability indirectly. (3) In the absence MCL radial head, if it is intact, replaced or repaired, provide stability to the elbow. (4)The radial head also provides axial support to the forearm and acts as an anterior buttress resisting posterior dislocation or subluxation.(5) Resection of radial head may result in ulna minus and disturb distal radio-ulnar joint When fragments are very small, less than 25% may be discarded and head need not be repaired. In the absence of radial head, over a time, MCL stretches out and LCL collapses, contracts and dynamic valgus deformity of elbow results.

Morrey et al[7] did cadaveric studies regarding the relationship of MCL and radial head. In the presence of an intact MCL, radial head resection did not cause any significant valgus instability. However, the removal of the MCL caused valgus instability even with an intact radial head. Removal of both resulted predictably in gross subluxation and severe valgus instability. They concluded that the radial head is an important secondary stabilizer of the elbow, as it contributes significantly to valgus stability in elbows with a deficient MCL. Corollary of this i.e. with absent radial head and restoration of MCL, LCL, coronoid, flexor – extensor muscular attachment and application of hinged external fixator, the elbow may be stable enough[6]; however this has not been studied biomechanically.

Fractures of antero-medial facet instability is due to the attachment anterior bundle MCL at sublime tubercle. The mechanisms of TT injuries can be divided into low-energy falls from standing height and high-energy accidents usually due to vehicular accidents. Most of the low-energy mechanisms are usually in elderly person with osteoporosis. The mechanism of failure is according to the “Horii” circle, where the sequential failure of soft-tissue constraints starts from the lateral side and moves anteriorly and posteriorly to the medial side.

Material and Methods

Twenty patients sustaining elbow dislocation with associated radial head and coronoid process fracture, over a period of 7 years between 2009-2016 were enrolled in the study and their clinical results were assessed. The series included 13 males and 7 females of mean age of 35 years (range, 15-58 years) at the time of trauma.

14 patients had sustained the initial trauma during a road traffic accident and 6 had a fall from height. 18 dislocations were closed injuries with no neurovascular deficits and 2 were open. The initial assessment included high quality antero-posterior(A/P) and lateral radiographs of the elbow. Diagnosis of TT can be easily made by noting elbow dislocation, fractures of coronoid and fracture of radial head by good radiographs. Prompt closed reduction of TT should be attempted. This will reduce pressure on the soft tissues and decrease the chance of subsequent secondary neurovascular compromise or compartment syndrome.

CT scan was performed routinely in all the cases to rule out any occult coronoid process fragment. CT helps to understand morphology, size, shape and displacement of all fragments and to plan surgical technique.

In all cases, it was a postero-lateral dislocation of the elbow joint associated with fractures of the radial head and coronoid process. We had 2 cases of TT associated with trans olecranon fracture dislocation. Both were approached through a long posterior approach. Our series included 6 type I fractures, 4 type II fractures, 10 type III fractures. When there is complete posterior dislocation, all the ligaments, anterior capsule and medial and lateral muscular attachments are torn.

Operative Technique

Dislocations were reduced by closed method in 8 patients and 12 were reduced by open technique under general anaesthesia and image intensifier. Final reconstructive surgery is done as early as possible.

Either a posterior global incision or a lateral incision was used. For a lateral approach supine and for posterior approach lateral decubitus position was used. In 14 cases lateral surgical approach was carried out through the Kocher[19] interval, between extensor carpiulnaris and anconeus muscle. In addition, a medial approach in 8 cases, which provides better access to the coronoid process and the medial collateral ligament. Posterior approach was performed in 6 cases.

TT with trans-olecranon fracture needed a long posterior approach. When posterior approach was used, a thick flap was raised to prevent skin necrosis. Proximal fragment of olecranon along with triceps was lifted up proximally, similar to olecranon osteotomy approach. The coronoid fragment can be approached through fracture site for passing ‘lasso’ sutures or lag screw/s. Radial head was repaired or replaced or resected as indicated. MCL and LCL also were repaired through the posterior approach.

Exploration revealed persistent damage to the lateral collateral ligament in all cases. In 8 cases, decision to reconstruct MCL was taken because at the end of surgery extension test showed some subluxation or doubtful stability.

In 5 cases of non-re- constructible type III radial head, excision was performed and no prosthesis was used, hinged ex fix was applied.

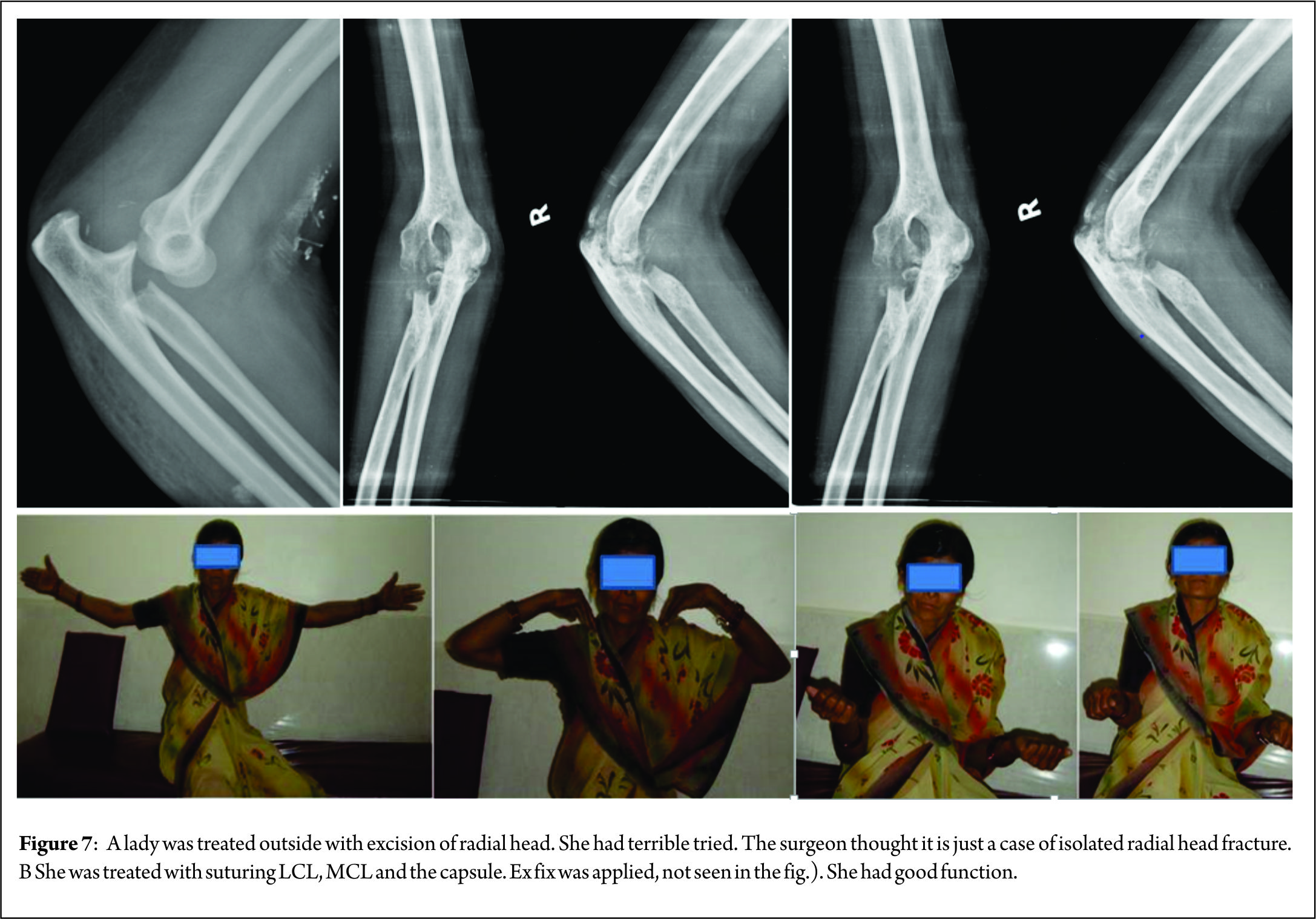

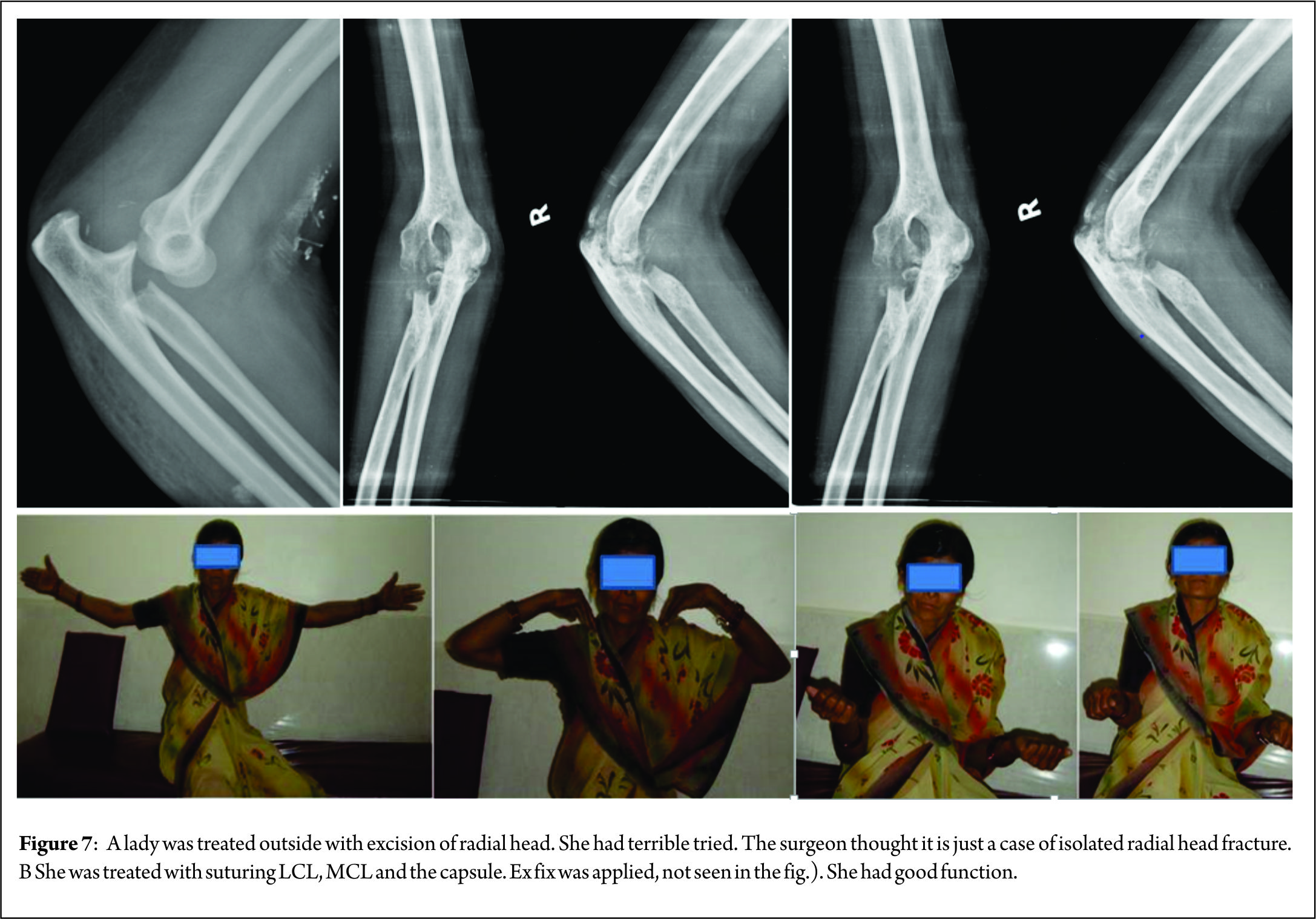

In 2 cases, the radial head was excised by outside surgeon. He missed the diagnosis of TT and thought the case to be just a case of isolated radial head fracture. At 2 weeks, both patients had instability and were referred to us. In these 2 cases with absent radial head, after reconstruction of all ligaments including MCL and coronoid, orthofix type hinged external fixator (Pitkar Orthotools Pvt. Ltd. Pune) was applied.

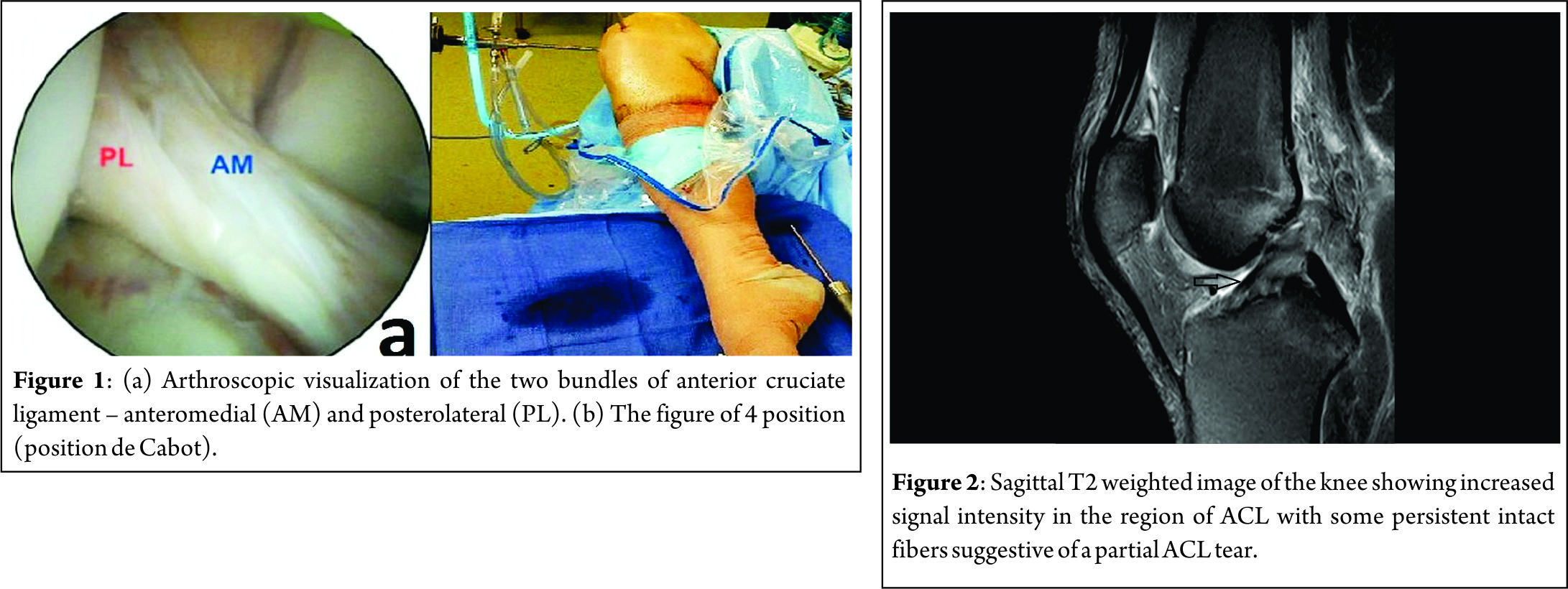

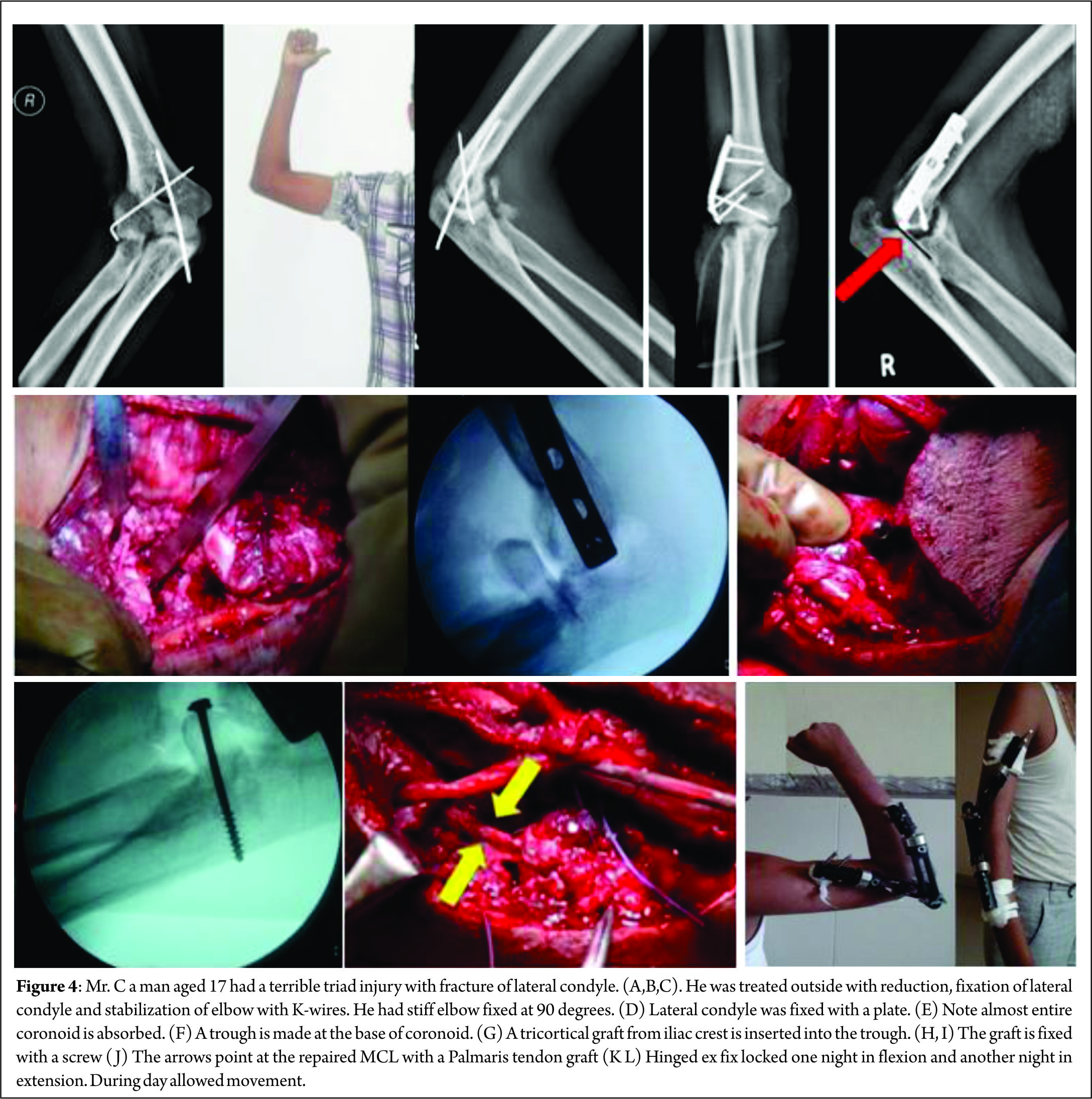

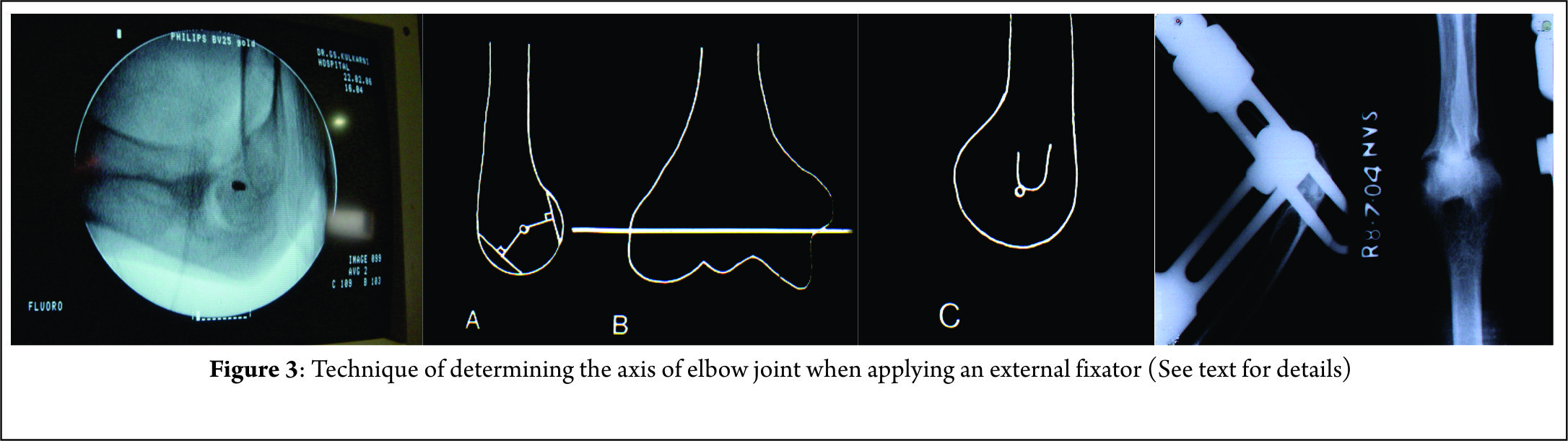

When one applies hinged external fixator, it is very important to see that the axis of external fixator is collinear with axis of the elbow joint. Axis of elbow joint passes through centre of lateral epicondyle laterally and through a point just anterior distal to medial epicondyle. We have developed a technique of matching axis of hinge and elbow. In a dead lateral view of elbow on image intensifier, the centre of the circle of capitulum represents the point of axis elbow on the lateral side. Axis point on the medial side is just distal and anterior to the medial epicondyle. Two K-wires are passed- one through the centre of lateral condyle and one through the point on the medial side described above (See fig.3.) The wires were cut 1 cm away from bone. When applying external fixator, the centre of external fixator is in line with both K-wires. After applying external fixator k-wire were removed from both sides.

Repair of radial head with 2.4mm Herbert screw (Synthes) was performed in 7 cases of type II fractures. Resection of radial head was done in 7 cases and in all these cases hinged external fixator was applied. Replacement was done in 6 cases.

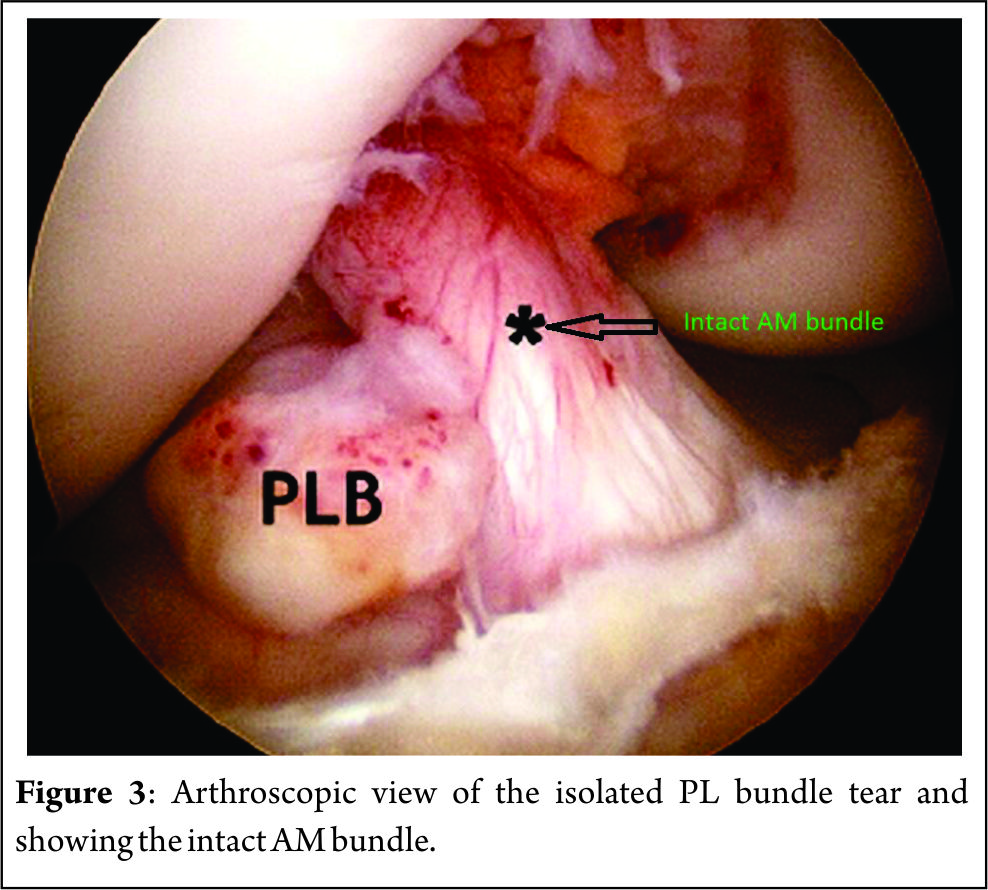

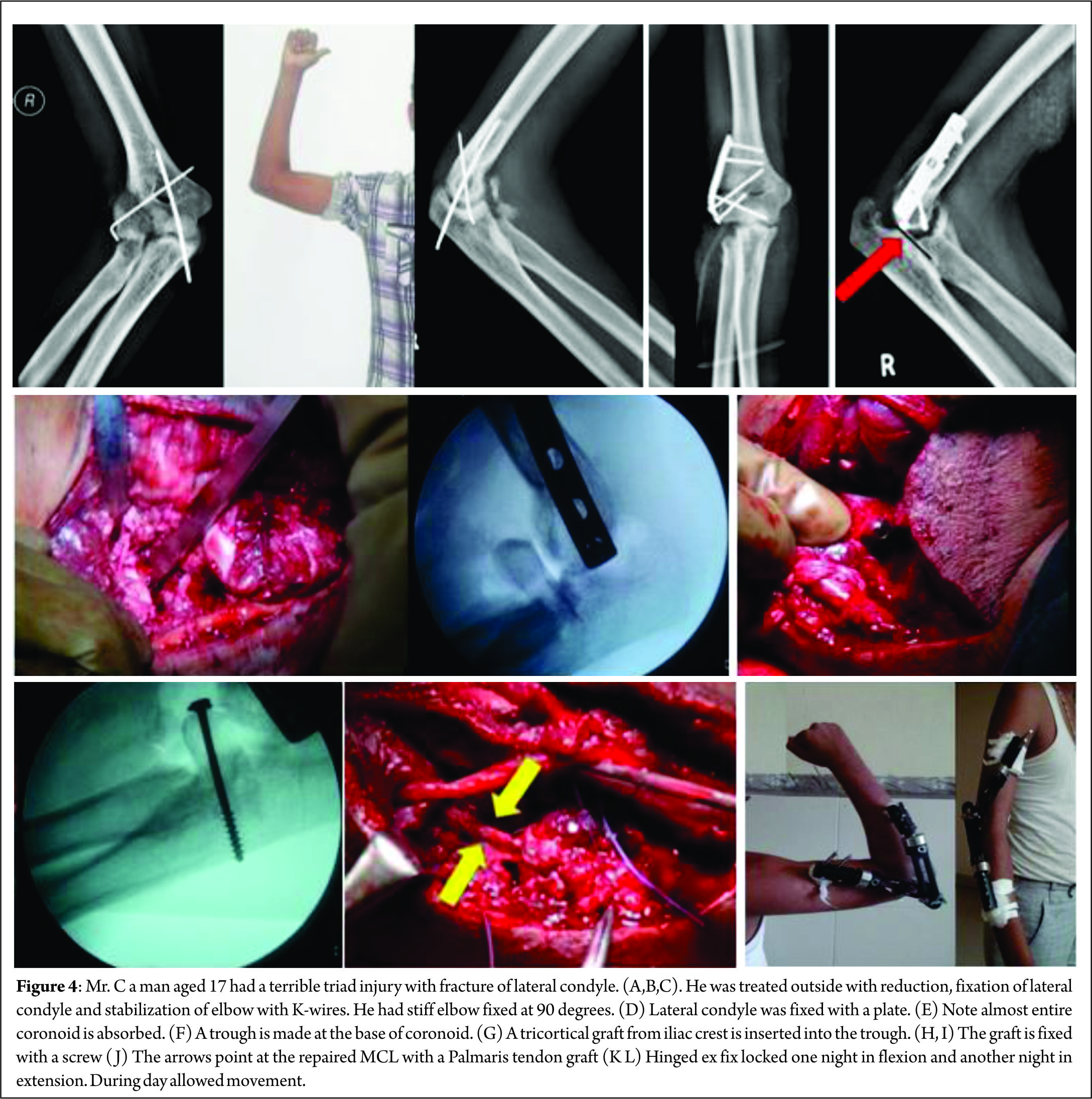

Five type I coronoid fractures were neglected. Eight type II coronoid fractures were treated with suturing the capsule with no.1 non-absorbable sutures. In one delayed case coronoid fragments were completely absorbed and was reconstructed with a piece from iliac crest (Fig.4.). All lateral and medial collateral ligaments were repaired with no.1 non-absorbable sutures.

At the end of the surgery, flexion – extension was tested from 30° to 110° of flexion. If there was instability during extension, MCL was repaired. In cases when MCL, LCL and coronoid were repaired and still there was some instability, orthofix type external fixation was applied. Indications for external fixator were radial head excision or instability at the end of surgery. Structures were generally addressed in a deep to superficial manner (coronoid first, then radial head, finally LUCL).

The coronoid was addressed with a suture ‘lasso’, suture anchor, or lag screw technique, depending on the size and comminution of the fracture fragment. Stability of the elbow was tested with the hanging arm test.

Post Operative Management

Elbow maintained at 90° in a posterior plaster splint. Elbow was mobilized passively from 45° to 100° flexion, 3 times in a day. Sutures were removed at 2 weeks. Patient was taught to do flexion-extension exercises passively from 45° – 100°. At 3 weeks active exercise were allowed and to slowly increased the range of motion.

When hinged external fixator was applied, during day the elbow mobility was allowed with hinge kept loose, and during one night hinge was tightened to maintain flexion at 90° and the next night it was tightened to maintain extension up to 135° (i.e. 45° short of full extension). This protocol has given excellent results.

When external fixator was not applied, continuous passive motion was started on post operative day 2 as per patients’ tolerance. Active pronation-supination movements were allowed with the elbow placed in 90° of flexion. Up to 6 weeks extension was limited to 30°-60° according to the elbow stability and to prevent the risk of dislocation. External fixator was removed at 6 weeks. At 3 months, muscular rehabilitation programme is initiated to strengthen the periarticular stabilizing muscles.

Devid Ring et al[20] to avoid varus stress of the elbow (shoulder abduction), used temporary external fixation (static or hinged) or temporary cross pinning of the elbow joint. When fixation is secure, stretching exercises can be started as soon as the patient is comfortable. Active self-assisted stretching exercises are key to regaining elbow and forearm motion. Static or dynamic splints may be used. Problems with internal fixation are stiffness, instability, or ulnar neuropathy. Infection is uncommon[20].

Evaluation

17 patients were reviewed at a mean follow up of 33 months (range, 18 to 60 months) and were clinically and radiologically evaluated. 2 patients were lost to follow up. One patient was followed up only up to 6 months. He had no pain and had functional range of motion from 30° flexion to 120°. Patients were clinically assessed according to the Mayo Elbow Performance score, on the basis of pain, mobility, stability and functional evaluation. Radiographic assessment of the elbow, based on A/P and lateral views was performed at last follow up.

Results

The mean Mayo Elbow Performance Score, at evaluation 18 patients was 86 (range, 75 to 100). The outcomes were classified as excellent in five elbows and good in 7, fair 5 and poor 1.

However, of great significance, delayed reconstruction the satisfactory outcomes decreased to 50%[21].

Ten patients had no pain while five reported to have mild pain on lifting heavy weights. 3 had negligible pain. None of the patients suffered from severe pain. Mean flexion at last follow up was 110°, ranging from 90° to 140°. Mean extension loss was 14, ranging from 0° to 80°. Mean pronation was 70° (range, 30° to 80°) while mean supination was 60° (range, 30° to 80°). Elbows were stable in flexion extension and varus-valgus in all the cases. One patient (See Fig.5.) returned 3 years after with pain on the lateral side of elbow. X ray showed reduced joint space at radio-capital joint. The radial head was excised. 2 years later after excision of head of radius, patient had no pain at elbow nor at distal radio ulnar joint.

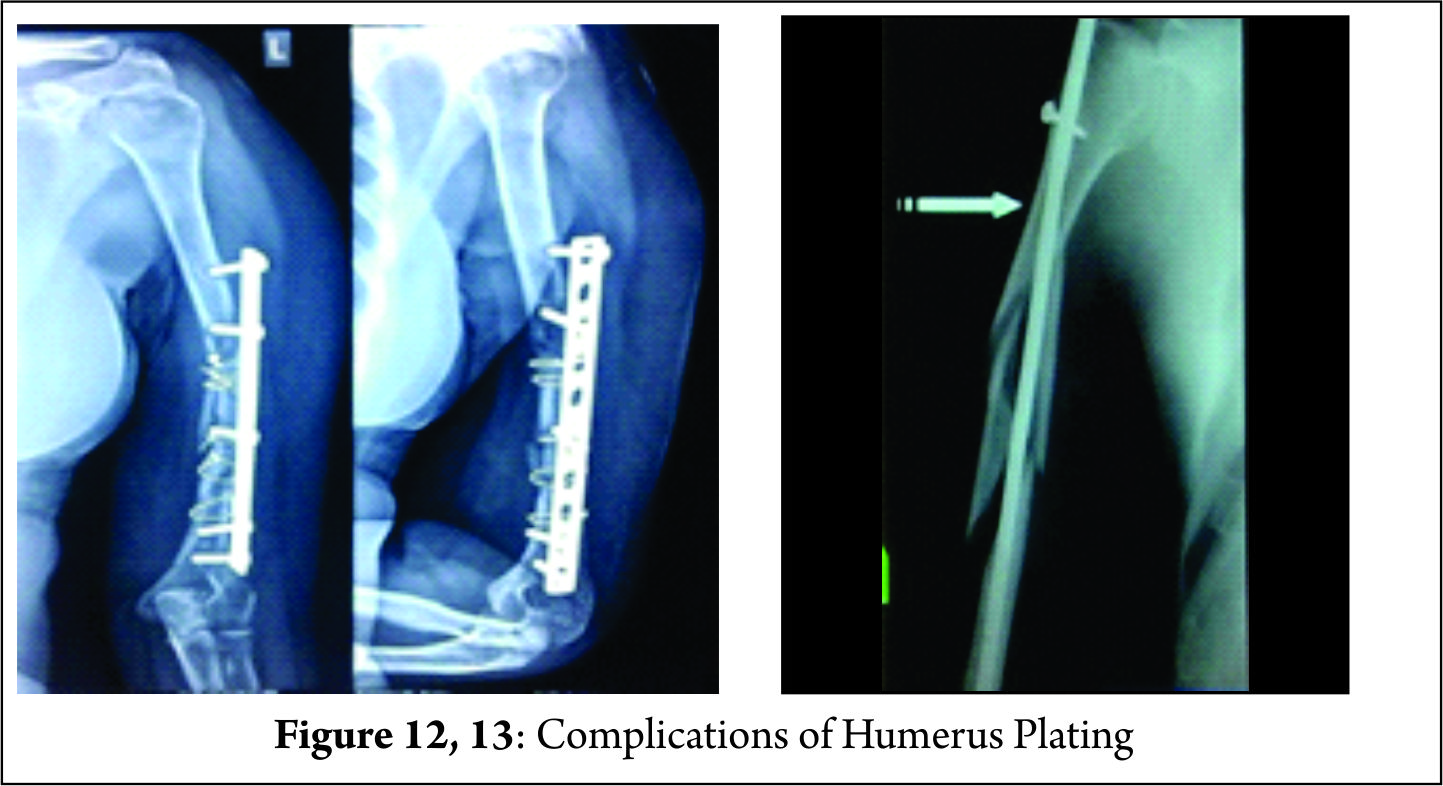

Complications

Early complication was in a 22 year old male patient who had a persistent instability in the sagittal and frontal plane, after suturing type III coronoid fracture with ethibond and no surgical intervention for type I radial head fracture and lateral collateral ligament was repaired. At one month, this persistent instability required surgical revision performed through a medial approach and revealing cut through of ethibond sutures used for coronoid process fracture, which required screw fixation and repair of MCL. An orthofix ex fix was applied at the end of the operation to stabilize the whole reconstruction. He did well but had some amount of stiffness. 11 patients also had reduced range of movements between 30° to 120°. Other complications like heterotopic ossification, ulnar neuropathy, errant hardware, or malunion were not noticed in any of the patients.

A late complication occurred in a 50 year old female patient with type III radial head fracture and type I coronoid process fracture operated through posterior approach and excision of radial head was performed. The patient developed posterior interosseous nerve palsy for which flexor carpiradialis tendon transfer was performed at 12 months after electrodiagnostic testing showed no signs of progression of regeneration. Wrist movements were restored (Fig.6).

Discussion

A systematic approach to management of TT injury of elbow that surgically addresses each individual component of pathoanatomy has resulted in improved results. The 3 components -coronoid, LCL and radial head are repaired. Adequate coronoid fixation in terrible triad injuries is of paramount importance. Radial head is either reconstructed with ORIF or replaced. Radial head resection has not been advocated in literature; however, Tanna’s [6] and our experience has shown that in Indian scenario, head can be resected in some situations (described below) with good results

Terrible triad injuries of the elbow have been described by Hotchkiss[1] in 1996 as a clinical entity. This condition accounted for 4% of adult radial head fractures and 31% of elbow dislocations in a study by van Riet and Morrey[22]. Complete dislocations of the elbow joint with radial head fracture should be considered as TT injury unless proven otherwise. This entity was named as ‘Terrible Triad’ by Hotchkiss because of the serious complications like recurrence of instability, stiffness, pain and chronic osteoarthritis. However, during the last 2 decades understanding the biomechanics of injury, complex pathoanatomy improved surgical technique, and primary and secondary factors, which stabilize the elbow, results, have improved considerably. Associated lesions represent a significant diagnostic and therapeutic issue.

CT scan assessment should be performed in every case. C.T gives excellent information regarding size, shape and displacement of each fragment and guide the surgeon to plan the surgery with most adapted therapeutic management.

Several retrospective series have been reported, with each reflecting differing injury patterns, operative strategies, and outcomes.

Most of these injuries are managed surgically. The principle of surgical management is based on two main objectives: Restoration of bony stabilizing structures (radial head and coronoid process) and lateral collateral ligament repair.

The commonly used surgical protocol for TT of the elbow injuries is well established as follows:

(1) (a) Coronoid plays a vital role as an anterior buttress therefore reduce and fix the coronoid fracture first, if it is more than 10% of coronoid height. Coronoid tip fracture with height < 2 mm may be neglected. (b) Coronoid fracture, type 2 O’Driscollis fixed with a screw or coronoid plate through medial approach.

(2) Radial Head; (a) repair if 3 or less pieces b) if comminuted replace or resect. If radial head is excised MCL, LCL and coronoid must be repaired with hinged external fixator applied. Head resection is controversial

(3) LCL complex and the common extensor origin are always repaired.

(4) MCL is not routinely repaired. Repaired when elbow is unstable as detected by tests at the end of surgery.

(5)If residual instability of the elbow joint persists, apply a hinged external fixator is applied.

Although this treatment protocol has been proved effective, instability, contracture, re-operation, and progression to arthrosis still may be significant problems. Proper counseling must be done.

Approach

Commonly used approach is by a long posterior incision. Advantages claimed are that it allows access to both the medial and lateral aspects of the elbow, and it precludes the need for a second medial skin incision; also it is cosmetic, less seen; Morrey[6] assumed that any coronoid fracture must cause some injury to one or both of the collateral ligaments. Hence, exposure usually involves a posterior incision from which surgeon can inspect each ligament complex as necessary. Ligament will typically heal if the ulnohumeral joint is reduced and stable[12].

However, posterior approach is associated with complications of skin edge necrosis, seroma, hematoma and a possible infection. Lateral approach has the advantage of a small incision and repair of coronoid, radial head and LCL can be safely managed; usually medial incision is not required, occasionally indicated to reconstruct MCL or medial wall fracture of coronoid. Stabilizing coronoid fracture is easier from medial side. Zhang et al[23] used an extended lateral approach in combination with a separate medial approach in every patient. An anteromedial skin incision was made and an ”over- the-top” approach was used to expose most of the coronoid fracture[23].

Resection of the head: Most of the authors suggest to repair or replace the radial head in the management of TT. The function of the radial head is to prevent valgus instability in the absence of MCL by abutting against capitulum. If radial head is excised and if there is MCL deficiency, gross valgus instability occurs. In isolated fractures of the radial head with comminution if excised, instability does not occur. Another important function of radial head is to tighten the LCL. In the absence of radial head LCL becomes loose. Morrey[18] has shown when the radial head is present and the collateral ligaments are intact up to 50% of the coronoid may be absent and the elbow will remain stable. Hence the value of either fixing the radial head fracture, if possible, or replacing the head with a prosthesis is clear in the presence of these specific associated injuries[12].

When the radial head is resected and even if the MCL, LCL, and coronoid both extensor or flexor muscles are repaired valgus instability may occur, if elbow is not fully immobilized because the repaired MCL, LCL are not strong enough to resist the valgus forces. In due to course of time MCL is stretched out and LCL is lax, valgus instability occurs. However, this can be prevented by a hinged external fixator, which protects the repair of the MCL, LCL and coronoid, till complete healing of all the reconstructions (MCL, LCL, and coronoid). They heal well at 6 weeks, when the external fixator can be removed.

If external fixator is not available, elbow should be immobilized by bridge plating as is done for distal end of radius or cross pinning is done. When all the repaired structures heal, elbow is stable even in the absence of radial head, a situation similar to resection of head for isolated radial head fracture. Thus, in management of TT the radial head can be excised provided all stabilizers are repaired and a hinged external fixator is applied properly as described above. Hinged elbow braces have a limited application as they rarely fit exactly, do not match the axis of elbow, and are prone to instability13. Cast immobilization is often insufficient.

In the Indian scenario,

1. Patients come late after injury, often >2 weeks

2. Proper sized radial head implants are not available

3. Patient cannot afford imported implants

4. Surgeon may not have the training of implant surgery

Prosthetic surgery has a high learning curve.

5. Poor infra structure

This situation made us to try resection and repair other structures with application of a hinged external fixator; it has given satisfactory results. Results of replacement are far from satisfactory, even in the hands of experienced surgeon and using modern modular prosthesis. Replacement needs refinement. Redial head repair is also associated with complications of stiffness of elbow and technically not so easy. Our results of excision of radial head with bony and ligamentous reconstruction are comparable. In our series, 7 radial heads were resected, with repair of all other primary and secondary stabilizers. Of the 7 cases, 6 had good stability and one resulting in intra-operative instability requiring additional stabilization with humeroulnar cross-pinning. In all other 6 cases, hinged external fixator (Ortho.fix) was applied. Two patients came with radial head already excised, by the previous surgeon who missed the diagnosis of TT and thought it just simple fracture of radial head (Fig.7).

In most of the literature, radial head excision is not advocated; However Tanna’s [6] and our small experience has shown that in Indian scenario, we suggest radial head excision with reconstruction of all 3 primary and 2 other secondary stabilizers with application of hinged external fixator, when it is not possible to repair or replace, though the literature does not support and the number of cases treated with excision is too small. Further study of resection of head in TT is strongly recommended.

Radial head repair

Radio-capitellar contact along with LCL repair is crucial to restore stability the management of Tt2.

2 or 3 large pieces of head of radius can be reduced and fixed with mini fragment countersunk lag screw/s 2.7 or 3 mm headless or Herbert screws are used. If associated with radial neck fracture, plate may be applied in the “Safe Zone” – lateral surface of head as seen when the forearm is neutral (mid prone) position.

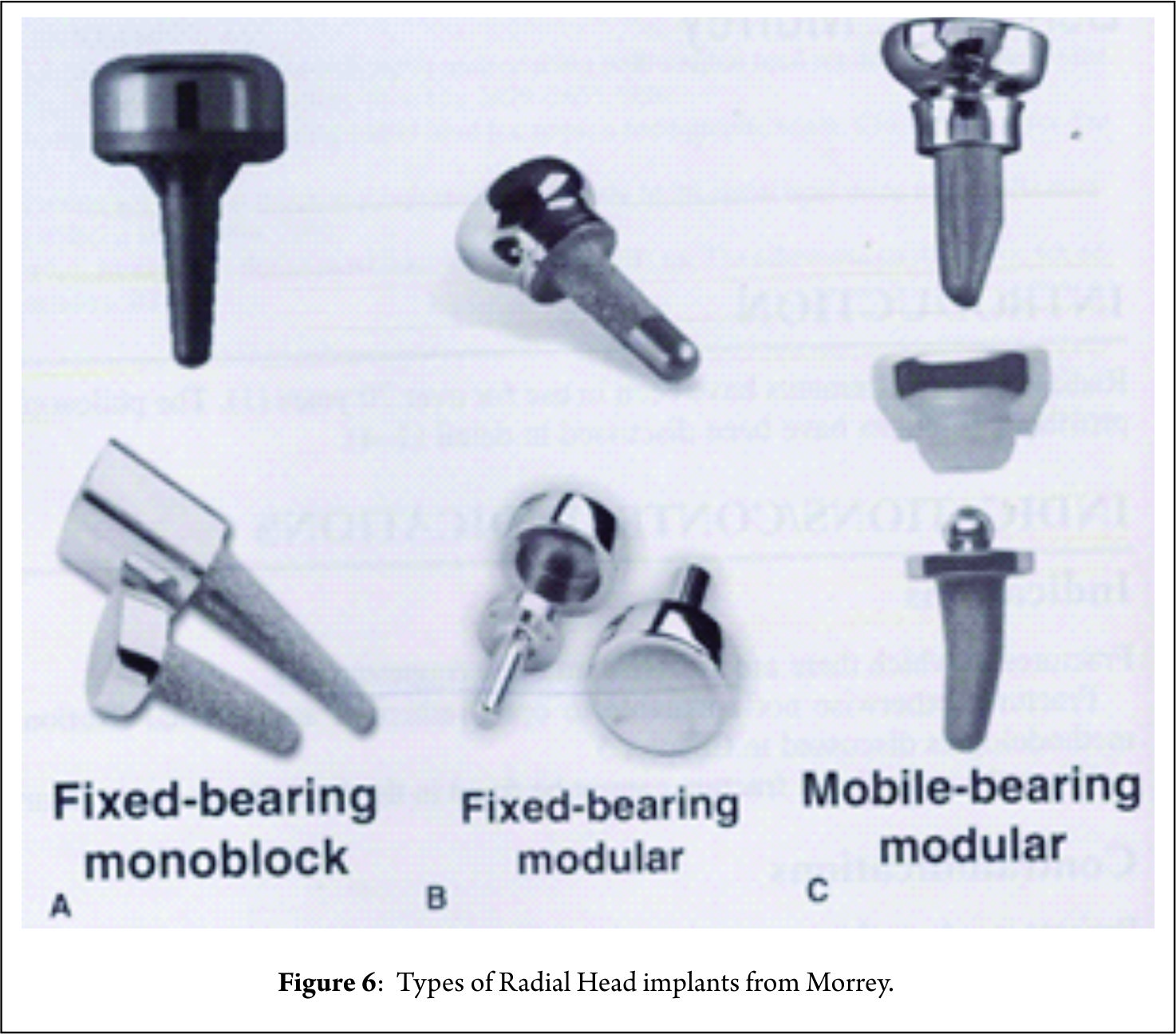

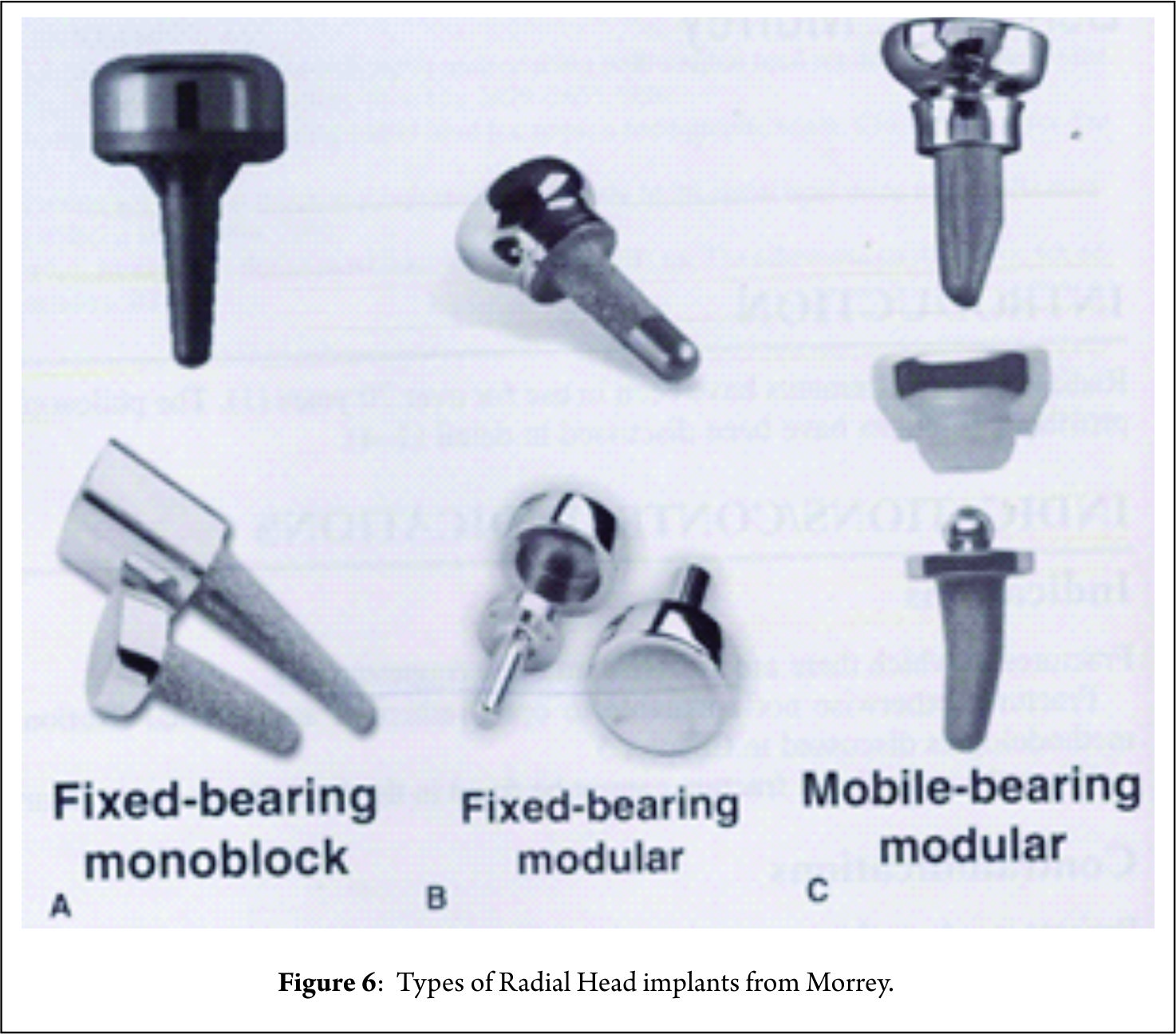

Radial head replacement

Radial head replacement is technically a difficult procedure in the treatment of TT injuries. Height, shape and size of the radial head should correspond to the height of the excised fragments; in cases of radial neck comminuted fractures under sizing of the removed head fragments is common, which can result in elbow valgus instability if accompanied by MCL injury. On the other hand, over sizing of the head fragments may cause overstuffing of the humero-radial joint, with the potential risk of stiffness and capitular erosion. Over stuffing of radial prosthesis necessitates reoperation. Properly sizing the radial head prosthesis can be challenging; and is performed with the elbow in extension, but the radiocapitellar joint is tighter in flexion than extension, which can lead to overstuffing. Also, biomechanical study has shown that no type of radial head prosthesis can restore elbow valgus stability to the same degree as was provided by the native radial head[24]. Arthrosis was more common in the arthroplasty group than in the ORIF group[25].

Tyler S Watters et al[25] reported that radial head arthroplasty has been shown to be a reliable technique for reconstruction of the radial head. The radial head prostheses interestingly were more stable and had a greater ROM when compared to ORIF. There was a learning curve for radial head replacement for proper head size selection, may result in overstuffed radiocapitellar joints. Excision of the radial head was strictly avoided without replacement[25].

The complications associated with prosthetic radial head replacement are similar to those for any prosthetic intervention; infection, loosening and osteoarthritis. The radial head implant impacts on the capitellar side of the joint resulting in erosion of the articular surface. The reasons for revision of prosthetic radial head replacement have recently been reviewed by van Riet et al[22]. The most common causes for subsequent intervention include loosening, instability and problems with articulation all of which are considered mechanical-type failures. The most common technical problem associated with these complications is failure to secure solid fixation of the stem. “Overstuffing” of the joint is one of the most common technical errors and leads to capitellar erosion and pain. It is also now recognized that the use of a radial head implant in the setting of a reconstructive surgery, or when there is associated injuries, is also associated with an increased incidence of complications[12].

Coronoid: The coronoid is clearly the most important articular stabilizer and key element in the humero-ulnar joint stability. 50% of the height of the coronoid process is necessary to ensure humero-ulnar sagittal stability. In TT injuries of the elbow, most coronoid fractures are type I fractures as confirmed by the series of Doornberg et al[14]. The anterior capsular attachment to the coronoid fragment or fragments should not be released because protecting the attachment enhances stability. Type II and III fractures require stable osteosynthesis, which might be performed through a lateral approach after radial head excision, or via a medial approach. In our series 6 type I fractures were ignored, 11 type II fractures were sutured to the capsule and 6 type III were fixed with screws or a plate through medial approach.

Isolated tip fracture: A tip fractures are sutured if fragment size amenable to repair (larger than 10% of coronoid height) via a lateral approach. If MCL was to be repaired, a medial approach was used. If the fragment is large (>10% coronoid height) it is fixed with a screw.

Anteromedial facet fracture: Fracture of the anteromedial facet of the coronoid process typically results from a varus posteromedial rotation injury force and is usually accompanied by an avulsion injury of the LCL [20].

Small anteromedial facet fractures are best repaired with a suture that engages the capsular attachment through a medial exposure. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of antero-medial facet is reliably stabilized with a screw or buttress plate that pushes the fracture fragment against the intact coronoid and deficient MCL is repaired. Medial approach is taken by separate medial skin incision. Pre-contoured buttress plate may be applied for comminuted fracture.

If the coronoid is severely comminuted and the fragments are loose or absorbed in the soft tissue, the coronoid is reconstructed by a tri-cortical graft from iliac crest. This usually occurs in patients with delayed presentation. (Fig.3.)

Basal coronoid Fracture:

Sub type I : Basal coronoid fracture is treated by ORIF by screw or a pre-contoured plate.

Controversy of coronoid tip fracture – Repair or not to repair?

Coronoid tip fractures are often associated with TT injuries, and rarely occur in isolation[26]. In many centres it is fixed [14], others have challenged this with biomechanical evidence suggesting that small (<10% of coronoid height) fractures contribute very little to stability, and any valgus instability should be addressed by repair of the MCL instead [14,26,27]. We have fixed tips only when it is > 10 %.

Terrible Triad with transolecranon fracture

Terrible triad transolecranon is a severe injury. The anterior translation of the forearm is the hallmark of this instability pattern and hence this injury is often referred to as a trans-olecranon fracture dislocation [28,29]. This is a Sub type II basal coronoid fracture of O’Driscoll classification. A large basilar fracture of the coronoid are nearly always associated with olecranon fracture–dislocations. Usually have a fracture of the radial head as well. Both the fractures are approached though the traumatic window of the olecranon by a long incision. A thick flap is raised to prevent skin necrosis. Care must be taken during handling of the ulnar nerve and while fixing coronoid for screw penetration into the ulnohumeral or proximal radioulnar joints. Olecranon fracture is fixed with a long plate [20] .

ULCL: The most important step in achieving stability is repair of lateral collateral ligament which is the primary stabilizer. Successful isometric repair is by placing the sutures at the centre of rotation of the elbow, which is located at the center of the capitular curvature on the lateral epicondyle and at supinator crest, to prevent the occurrence of any varus or postero-lateral instability.

MCL:

Systematic approach of medial collateral ligament remains controversial. Injuries to the MCL, which have been reported in 50–60% [13] of TT injuries, are not universally repaired. Forthmann [30] argues that MCL injuries tend to heal by scarring in simple elbow dislocations, and the repair of articular (and LCL complex) injuries in TT will effectively transform this injury into that of a simple dislocation, thereby rendering MCL repair unnecessary.

After repair of the coronoid process, radial head and lateral collateral ligament, the elbow should be fluoroscopically examined for stability, while it is flexed and extended with the forearm insupination, neutral position and pronation.

In 2004, Pugh et al [27] reviewed 36 TT injuries out of which isolated lateral approach was used in 26 cases. Radio-capitellar contact along with LCL repair is crucial to restore stability [2].

Their surgical protocol included fixation or replacement of the radial head, fixation of the coronoid fracture if possible, repair of associated capsular and lateral ligamentous injuries. After reconstruction of the lateral ligament complex, stability of elbow was evaluated in flexion-extension. In the absence of instability, the medial approach was not performed. In case of instability, a medial approach was chosen for reconstruction of the ligament complex and an external fixator was placed in some patients. The authors advocate that a medial approach should be performed only in case of persistent sagittal instability after reconstruction of bony structure and lateral collateral ligament. They recommend that isolated valgus instability in the coronal plane does not require medial collateral ligament repair as far as the elbow remains stable in flexion-extension.

Mathew et al [31] advocated that if the elbow remains congruous from approximately 30 degrees to full flexion in one or more positions of forearm rotation, repair of medial collateral ligament is not necessary. In our series, thirteen out of fifteen elbows treated through a medial approach reported damage to the medial collateral ligament. When radial head is excised MCL repair is mandatory

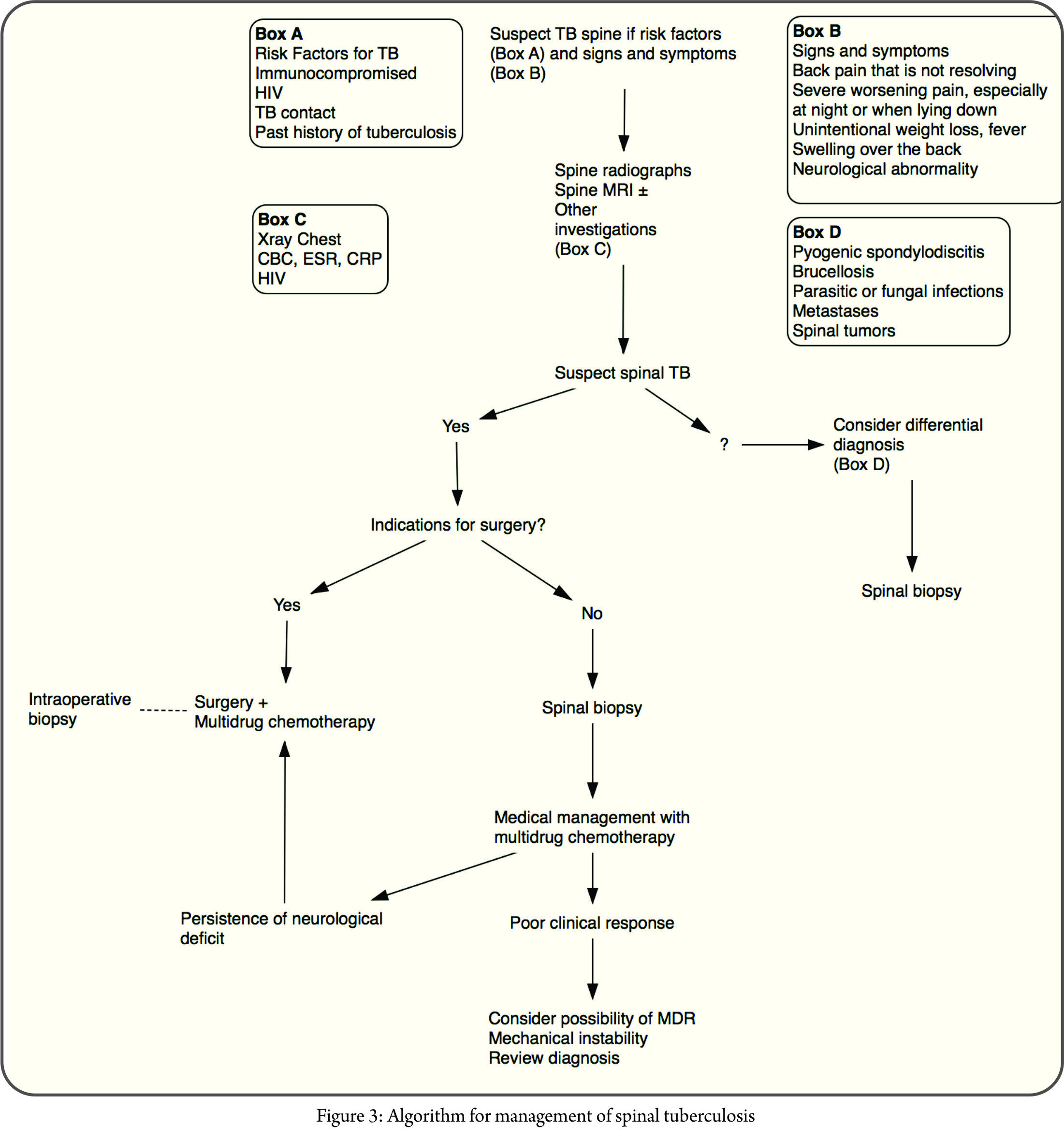

External Fixator

If instability persists despite repair of radial head and repair of the coronoid process, medial collateral ligament, or lateral collateral ligament, a static or hinged external fixator should be applied to maintain a concentric reduction of the elbow. Zeiders et al [32] have recommended the use of the external fixator in case of insufficient stability to allow complete mobilization after reconstruction of bony and ligamentous structures. These standard hinged external fixators are centered on the elbow centre of rotation. The external fixator allows early mobilizations within a protected range of motion to reduce the risk of secondary stiffness. In our series, we have invariably used hinged external fixators and reported that it prevents recurrent instability and protects reconstructed ligaments and soft tissue. External fixator is also indicated when radial head is excised. As shown in fig 4, fixators are also useful in neglected cases of terrible triad where the elbow is stiff [33].

Literature review

Zhang [2] from MGH Boston published an excellent paper on TT in July JOT 2016. One hundred of the 107 patients (93%) treated with open fixation of terrible triad injuries had no radiographic subluxation, so called drop sign. Five patients (5%) had persistent radiographic subluxation, 3 treated with a second surgery (3%). They concluded that Radiographic subluxation is very uncommon (2%) with current operative management of terrible triad injuries of the elbow within 2 weeks. They identified 2 risk factors or post-operative instability – (1) Delay of >2 weeks after injury, (2) Obesity. They suggested Patients treated more than 2 weeks after injury might benefit from ancillary fixation to limit subluxation (ie, cross pinning, hinged external fixation, or bridge plating).Modern techniques have decreased the incidence of post patient instability and other complications. Patients with higher BMI may be at risk for postoperative subluxation.

Yang et al[34] in 2013 reviewed 11 patients with TT of the elbow treated with hinged external fixator combined with mini-plate followed up to 12-20 months(mean, 15 months). According to Mayo elbow function evaluation standard, the results were excellent in five cases and good in four cases, and fair in two cases, with an excellent and good rate of 81.8%[4]. In 1 study, 11 patients with a terrible triad pattern, five of the elbows re-dislocated after operative treatment (including all 4 that had a radial head resection). The suture lasso technique was more reliable than the other techniques. The repair progresses from deep to superficial (coronoid, radial head, LCL) on the lateral side. The authors therefore favor fixation of the coronoid with a suture lasso except in the unusual case where the coronoid fracture is relatively undisplaced or stable[20].

In 2010 Chemama et al[35] published the results of 14 patients who were examined on an average of 63 months after injury. Several medial-sided ligament repairs were performed and motion results were similar to those of the current study, with an average flexion-extension arc of 18° to 127°. Mayo elbow performance score was 87 classified as excellent in 4 cases and good in 10.

There are limitations of this study. First, the number of patients was relatively small. Second, the study is not a randomized study. Third, though we have suggested radial head resection, the number of cases is too small and there are no biomechanical studies. On the other hand, the results showed that the technique provided good results with minimal morbidity. Considering review of literature and our own satisfactory experience, the TT of elbow is now no more terrible.

Conclusion

“Terrible triad” elbow fracture dislocation remains an unusual and challenging injury to treat. CT scan should be performed in all the cases to identify fracture patterns, comminution, and displacement. Surgical management is based on restoring the bony anatomy (radial head and coronoid process) and reconstructing (lateral collateral ligament) of the elbow to provide enough stability. A medial ligament reconstruction is indicated in cases of persistent instability. Although posterior approach has low risk of skin necrosis and is popular, we prefer lateral approach and when needed medial approach. Radial head excision is indicated in severely comminuted head in the situation prevailing in developing countries, mentioned above. Careful fluoroscopic examination of the elbow to assess any residual instability at the end of surgery and to determine the best position for immobilization as well as the safe arc of motion; Use of hinged external fixator is indicated when residual instability is detected at the end of surgery and in cases when radial head is resected; since it maintains reduction of the elbow and offers early mobilization. Optimal rehabilitation protocol is useful in allowing early motion while maintaining stability. With this modern treatment, the results of TT are satisfactory and TT is no more a terrible triad.

References

1. Hotchkiss RN. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow. In: Court-Brown C, Heckman JD, Koval KJ, Wirth MA, Tornetta P, Bucholz RW, eds. Rock-wood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996.

2. Dafang Zhang, Matthew Tarabochia, Stein Janssen, David Ring, Neal Chen. Risk of Subluxation or Dislocation After Operative Treatment of Terrible Triad Injuries. J Orthop Trauma 2016;30(12):660–663.

3. McKee MD, Pugh DM, Wild LM, et al. Standard surgical protocol to treat elbow dislocations with radial head and coronoid fractures. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005;87:22–32.

4. Gupta A, Barei D, Khwaja A, et al. Single-staged treatment using a standardized protocol results in functional motion in the majority of patients with a terrible triad elbow injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2075–2083.

5. Chen NC, Ring D. Terrible triad injuries of the elbow. J Hand Surg. Am. 2015;40:2297–2303.

6. DilipTanna. Elbow dislocation with irreparable fracture radial head. I.J.O. May 13;47(3);283-7.

7. Morrey BF, An KN. Stability of the elbow: osseous constraints. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al]. 2005;14(1 Suppl S):174S-8S.

8. Cohen MS: Fractures of the coronoid process. Hand Clin 2004;20:443-453.

9. Fornalski S, Gupta R, Lee TQ: Anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow joint. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2003;7:168-178.

10. Mason ML: Some observations on fractures of the head of the radius with a review of one hundred cases. Br J Surg. 1954;42:123-132.

11. Regan W, Morrey B. Classification and treatment of coronoid process fractures. Orthopedics 1992;15(7):845–8.

12. Bernard F. Morrey. Fractures of the Coronoid. Chapter 7 in Masters techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery; The Elbow, 3rd Edition (2015); Wolters Kluwer Pg.105 – 116.

13. Payam Tarassoli, Philop McCann, Rouin Amirfeyz. Complex instability of the elbow. Injury Int. J. Care Injured 48 (2017) 568-577.

14. Doornberg JN, Ring DC. Fracture of the anteromedial facet of the coronoid process. J Bone Joint Surg. Am 2006;88(10):2216–24.

15. Mezera K, Hotchkiss RN: Fractures and dislocations of the elbow, in Rockwood CA Jr, Green DP, Bucholz RW, Heckman JD (eds): Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, ed 5. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 2001, pp 921- 952.

16. Beingessner DM, Stacpoole RA, Dunning CE, Johnson JA, King GJ: The effect of suture fixation of type I coronoid fractures on the kinematics and stability of the elbow with and without medial collateral ligament repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:213- 17.

17. Closkey RF, Goode JR, Kirschenbaum D, et al. The role of the coronoid process in elbow stability. A biomechanical analysis of axial loading. J Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000; 82 A: 1749–1753. 187–195.

18. Morrey BF, Tanaka S, An KN. Valgus stability of the elbow: a definition of primary and secondary constraints. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;265.

19. Kocher T. Operations at the elbow. In: Kocher T, ed. Textbook of Operative Surgery. London: Adam and Charles Black; 1911:313–318.

20. David Ring, Taylor Horst. Coronoid fracture. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:437–440.

21. Bernard F. Morrey. Radial Head Prosthesis. Chapter 6 in Masters techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery; The Elbow, 3rd Edition (2015); Wolters Kluwer Pg.95-104.

22. Van Riet RP, Morrey BF. Documentation of associated injuries occurring with radial head fracture. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008;466(1):130-4.

23. Chi Zhang, Biao Zhong, Cong-Feng Luo. Treatment strategy of terrible triad of the elbow: Experience in Shanghai 6th People’s Hospital. Injury Int. J. 45(2014) 942 – 948.

24. Leigh WB, Ball CM. Radial head reconstruction versus replacement in the treatment of terrible triad injuries of the elbow. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery / American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al]. 2012;21(10):1336-41.

25. Tyler Steven Watters, Grant E. Garrigues, David Ring, and David S. Ruch. Fixation Versus Replacement of Radial Head in Terrible Triad: Is There a Difference in Elbow Stability and Prognosis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2128–2135.

26. Ring D. Fractures of the coronoid process of the ulna. J Hand Surg. Am 2006;31(10):1679–89.

27. Pugh DM, Wild LM, Schemitsch EH, King GJ, McKee MD. Standard surgical protocol to treat elbow dislocations with radial head and coronoid fractures. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2004;86-A(6):1122-30.

28. Ring D, Jupiter JB, Sanders RW, Mast J, Simpson NS. Transolecranon fracture dislocation

of the elbow. J Orthop Trauma 1997;11(8):545–50.

29. Mouhsine E, Akiki A, Castagna A, Cikes A, Wettstein M, Borens O, et al. Transolecranon anterior fracture dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007; 16(3):352–7.

30. Forthman C, Henket M, Ring DC. Elbow dislocation with intra-articular fracture: the results of operative treatment without repair of the medial collateral ligament. J Hand Surg. Am 2007;32(8):1200–9.

31. Mathew PK, Athwal GS, King GJ. Terrible triad injury of the elbow: current concepts. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2009;17(3):137-51.

32. Zeiders GJ, Patel MK. Management of unstable elbows following complex fracture-dislocations–the “terrible triad” injury. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2008;90 Suppl 4:75-84.

33. Kulkarni GS, Kulkarni VS, Shyam AK, Kulkarni RM, Kulkarni MG, Nayak P. Management of severe extra-articular contracture of the elbow by open arthrolysis and a monolateral hinged external fixator. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Jan;92(1):92-7.

34. Yang Y, Wang F. Hinged external fixator with mini-plate to treat terrible triad of elbow. Chinese journal of reparative and reconstructive surgery. 2013;27(2):151-4.

35. Chemama B, Bonnevialle N, Peter O, Mansat P, Bonnevialle P. Terrible triad injury of the elbow: how to improve outcomes? Orthopaedics & Traumatology, surgery & research (OTSR): 2010;96(2):147-54.

| How to Cite this article: .Kulkarni GS, Kulkarni V, Kulkarni R, Kulkarni S, Kulkarni M. Terrible Triad – Terrible Triad is no more terrible! Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics Jan – June 2017; 2(1):14-26. |